HSR Home

HSR Archives

Submissions

Past EditorsContact Us

Commentary on HSR

Hamilton Stone Editions Home

Our Books

Issue # 38 Spring 2018

Halvard Johnson Commemorative Issue

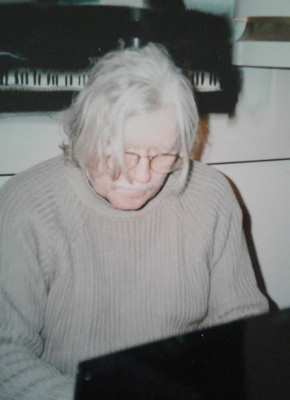

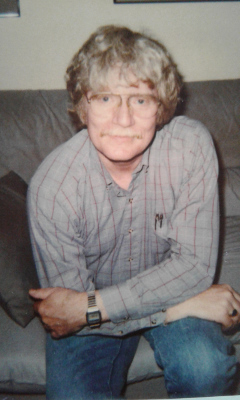

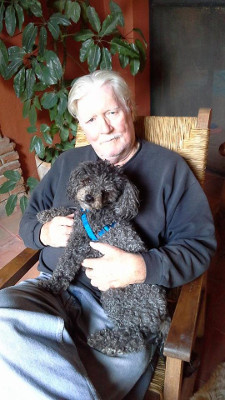

The poet Halvard Johnson died last fall at his home in Mexico. For many years he was the Poetry Editor of Hamilton Stone Review, an online review devoted to contemporary literature. Hamilton Stone Review is part of the co-operative publishing house Hamilton Stone Editions, where Hal was a founder and member of the Executive Board. Hal’s friends at HSE want to pay homage to this remarkable and gifted poet and fiction writer by dedicating Issue 38, The Halvard Johnson Issue, to his memory.

Hal's wife, fiction writer and visual artist Lynda Schor, also a member of the Hamilton Stone co-operative, gave us immeasurable help in putting this issue together.

James Cervantes

Burt Kimmelman

Roger Mitchell

Carole Rosenthal

Meredith Sue Willis

Contents:

(Click to go directly to the section)

Hal in His Own Words

Bio(psy)

“Nothing is more irritating than those works which

‘co-ordinate’ the luxuriant products of a mind that

has focused on just about everything except a system.”

--E. M. Cioran

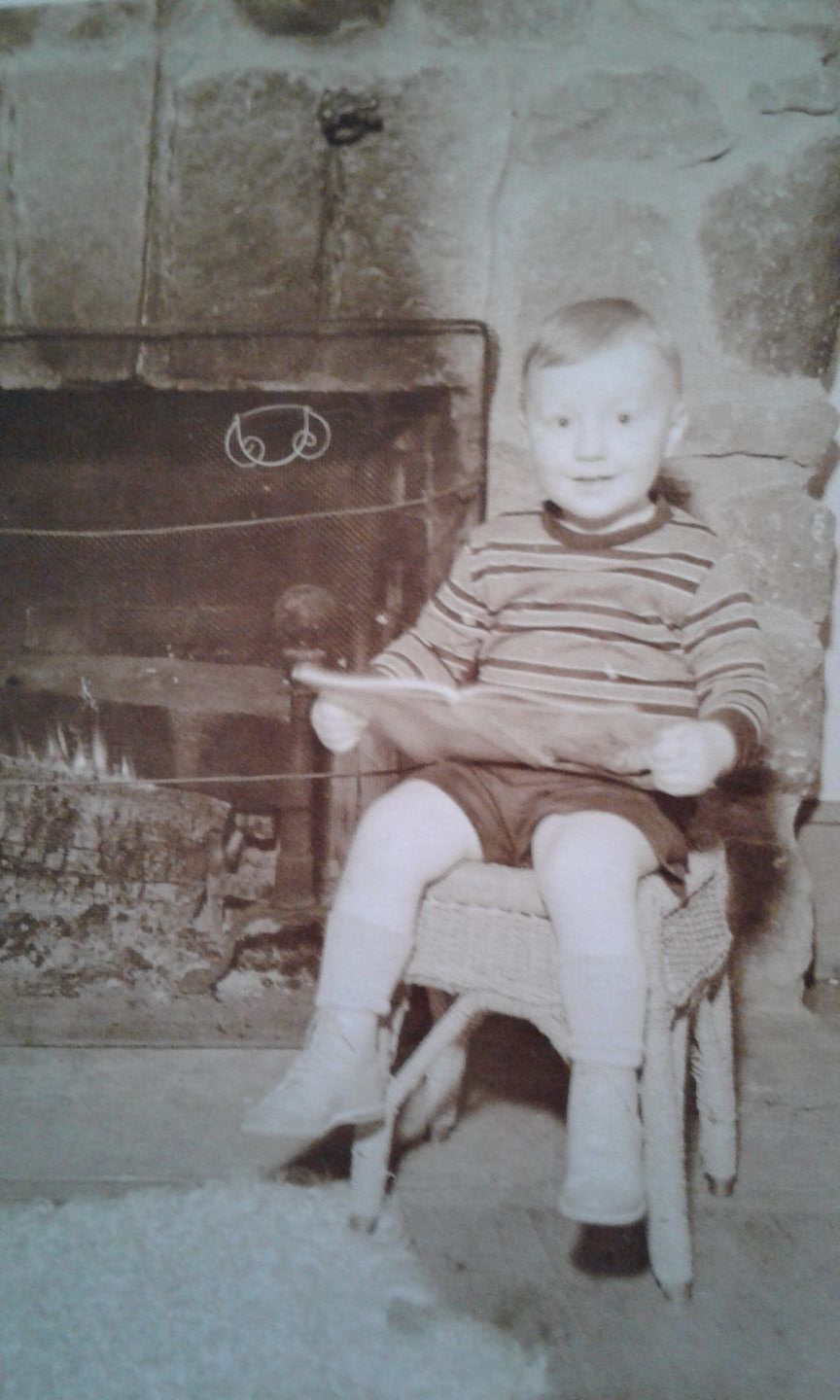

What is there to know about Halvard Johnson? He was born in Newburgh,

New York, in 1936, the son of a Methodist minister and his wife. He lost his

childhood in New York City and in small towns in the Hudson Valley--

Middletown, Kingston, Yonkers. He also lost his religion. For years he was

limited to walking, running, and sleigh-riding--until he took up biking. When

he was delivering newspapers, he passed long, hot summer afternoons riding

out onto the black-dirt flats just outside Kingston, New York, learning that

being lost didn’t matter as long as one knew where one was.

In 1955, he graduated from high school in Yonkers, New York, (just outsideNew York City) and traveled to central Ohio, where he pleasantly passed the

next four years at Ohio Wesleyan University, waiting on tables at a local

restaurant and learning a lot about the finer points of playing Ping Pong. He

majored in English and philosophy there, learning little about either.

He spent the summer of ’58 hitchhiking around the US, and the following year

experimenting with a nine-to-five life in NYC before setting off to do graduate

study at the University of Chicago, where he lucked into an MA in English and

began to earn his so-called living as a teacher of composition, recomposition,

decomposition, and sometimes littering . . . I mean, literature.

The autumn of 1964 saw him driving into El Paso, Texas, to begin a four-yearstint teaching Miners. Then, in 1968, as friends went off to Chicago to be

bludgeoned by the local constabulary, he shipped off to Puerto Rico, where,

in a little mountain town called Cayey, he dozed through faculty meetings

conducted entirely in Spanish, and taught classes in which students who had

just come to Puerto Rico from New York and couldn’t speak a word of Spanish

sat right next to students who lived fifteen minutes away from Cayey, couldn’t

speak a word of English, and had never even been to San Juan. During these

Puerto Rican years, he put together and had published his first of four

collections of poems.

Four years later, Johnson was on the move again. This time to Europe, wherehe and his wife spent a year as vagabonds, wandering the roads of Germany,

Austria, Yugoslavia, Greece, Italy, and Switzerland in a Volkswagen camper.

In 1973, he began to teach for the University of Maryland at various army

posts and airbases in Germany and, briefly, in Turkey, transferring to Asia to

do more of the same in Japan and South Korea.

In 1984, he returned home to the US (you can go home again) and resumedhis East-Coast life, along with all his childhood allergies to . . . well, you name

it--dogs, cats, trees, grass, mold, the poetry of Rod McKuen, and so. His years

abroad had left him permanently twisted, permanently bent--always able to see

the US as being every bit as weird and strange as anywhere else he’d ever been.

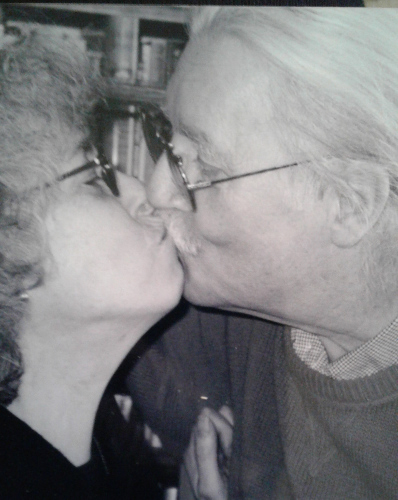

At the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, anartists’ so-called colony just north

of Lynchburg, Virginia, in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, he met

Lynda Schor, a writer and artist he is delighted and amazed to be the hubby of.

Together Johnson and Schor shared ten years in Baltimore, before cutting their

ties (almost all) there, and removing to New York City, where they live today in

an apartment house just a short walk from the apartment house Johnson lived in

as a boy, and from PS 41, where he attended kindergarten and first grade. It’s

also only a few blocks from the dismal walk-up on Morton Street where Johnson

lived during most of his “nine-to-five” year.

Let’s see, what else? Oh, there’s his so-called career as a writer . . . as a teacher. . . as a writer. Well, let’s be kind. He has a taxman who doesn’t snicker when

he identifies himself as a writer/teacher, even though the amount of money he’s

made from writing is roughly equivalent to the amount of money he’s found on

sidewalks and in parking lots. Back in the late 60s, he was walking along the Rio

Grande with someone who suggested he send a manuscript to someone. And over

the next ten years or so four slim volumes were published. These you can find

online at the Contemporary American Poetry Archive. There’s Changing the

Subject, which consists of poems Jim Cervantes and he wrote online at the Blue

Moon Cafe listserv over a period of six or seven thrill-packed weeks back in the

summer of 2002. That book was published on genuine hold-in-your-hands paper by

Red Hen Press in Los Angeles. It’s also available via Amazon.com, etc. There are free

online chapbooks available at xPress(ed).

Appendix: For what it's worth (FWIW), Johnson would be mad as hell to read that

his life after all that's written above has been a mere appendix to that, and he'd probably

be right in feeling that way. It's just been a few years since most of that was written,

during which time Lynda and he have discovered (for her) and rediscovered (for him)

Mexico, where they've been spending more and more of their time in San Miguel

de Allende in the state of Guanajuato. San Miguel (SMA) lies on mountain slopes

in the central highlands of Mexico, at an altitude of about 6,300 feet--about one

foot for every gringo in a town of 80,000, most of them complaining about how

many gringos there are in town nowadays (compared, say, to the late 40s, when

there were maybe five or six, most of them complaining about how many gringos

there were in town). Johnson's usual snide response to such complaints is, "If you

want to see a lot of gringos, try living in New York."

Selected Poems by Halvard Johnson

Poems chosen by Lynda Schor

A Bad Day from Winter Journey (1979, reissued 2015)

This was going to be my day

But my alarm clock didn’t go off

And I woke up very late

I dressed in a hurry, but still

had to skip breakfast. I left

home without kissing the missus.

I slipped on some ice and broke

an ankle. The pain was something

awful. The taxi that was taking me

to the hospital blew a front

tire and spun into a lamp post. The

driver was instantly killed, and I

had a broken arm and leg to go

with my broken ankle. An ambulance

came and took me to the hospital,

where everything was properly

set, and I was strung up in bed

like a puppet. At two o’clock

in the afternoon, a careless smoker

started a fire in the maternity

ward. Most of us patients were fully

evacuated, but a dozen or so babies

were killed or otherwise damaged.

Twenty-five other patients died,

some of whom were dying anyway. Ten

doctors and nurses were injured or

killed, and three firemen died of smoke

breathing. Police units were trans-

ferring us to another hospital when word

came that a series of explosions set

off by terrorists had wounded or killed hun-

dreds of people in the city. The

hospitals were jammed. I found myself

stretched out on the hardwood floor

of a high school gymnasium. The mis-

sile attack came without warning,

not even a blip on the radar screen.

The school was 90% destroyed, and most

of my fellow sufferers were 100% dead.

With my one good arm I managed to claw

my way out into the street, dragging

my useless legs behind me. To my

amazement, I found that this high school

was only a block from where I lived.

There was no one around, so, very painfully,

I inched my way home. No sign of the missus

there. The house was a shambles,

but the second floor was pretty much

intact, although somewhat lower.

Part of it drooped into the cellar.

My room was a mess. I hadn’t had time

to straighten up. So, screw it, I said,

and crawled back into bed—which,

of course, I never should have left.

Spam Sonnet from Remains to be Seen (2013)

A la recherché de’un emploi? You won’t ever have to explain

your flaccidness to her again. You can have the meds you need

for 70% less. Looking for a new foundational opportunity?

Do you want scientifically to debunk the Bible? You can view

this message as a website here. Hi man, was thinking of the old

times and thought of you. Sign in here to chat awhile. Replica

watches, direct from manufacturers. Spanish fly? This may solve

the only real problem you have. Anyone with sufficient work

experience can become a CEO. Do you prefer to spend less,

get more? Don’t let food be your greatest concern. Nothing

heals better! Beautiful Russian women are eager to meet you!

The Story So Far from Large Floating Objects (2017)

Past accelerations no guarantee of future ones.

Even a fraction of an imagination leaves some thing out,

to be desired, to be sought for unceasingly until . . .

well, until the tableau vivant is ready to be served.

All the silent streets swept clear of whatever the wind

blew in, howling in anguish, needing to be heard.

Nova from Winter Journey (1979, reissued 2015)

If it were up to me,

I would let you see everything.

You could tour the universe,

witness the end and the beginning.

You could feel what it’s like

to be sucked into a black hole

and spit forth on the other side.

You could explode like a nova,

feel yourself hurtling out from a center,

bright and fast, at incredible speeds,

in the darkness of space, scattering light.

Poems chosen by Burt Kimmelman

From Remains to be Seen (2013)

Your Emergency Preparedness Kit

What you’ll need in your kit, of course, depends on the kind

of emergency you plan to have and where you plan to have it.

If you’re in France and plan to have an emergency on the road

Be sure to take along a corkscrew, five bottles of wine, three or

four baguettes, some fine, pungent cheese, and a red and white

checkered tablecloth. In much of the rest of Europe and in Cali-

fornia, mostly the same. In Latin America, much the same, But

in Canada be sure to have a charged cell phone, and in the US

a fistful of credit cards, and your Triple-A card. A six-pack of beer

would be a comfort. In many parts of the world you can rely on

friendly locals to pull you out of a ditch, give you a push, or carry

you, your wife and kids off to a nearby clinic or hospital. In case

of serious injuries, it’s a good idea to have several units of blood

for each of you. And in Texas, of course, you’re on your own.

What Your Doctor Knows

Know ledge you often hate on first hearing,

coming to love as it grows into you. Perfect

anecdotes in spite of all your tense

accusations, while, despite the wallflowers

gang-banging the geraniums, a wild kitten

careens in your heart, love by second sight.

The greater the yearning, the greater

the grief. Impractical accident, with a difference.

Tropismes

There you are again, simple choices

by way of explanation. A closer look

revealing almost nothing.

Carrying across a range of contexts

some semblance of yourself.

Shattered glass, unrecognizable

patterns on the roadway,

Wanting something enough to take

steps to get it.

I Think Continually

I think continually of those who are truly great

Chinese poets, or might have been had they not been

born somewhere else, in some other time, wanting

but wanting to be Chinese, to float tiny little

poems out onto tiny little streams and then get drunk

As a skunk, hours into the newest of new millenniums.

I think sometimes of those who are always left out

of my thoughts, the ones I find it hard to imagine—

their pleasures and their miseries, their songs and their sufferings.

I sometimes think it’s almost enough to have thought

of them, but then that peasant behind the door,

The one with the sledgehammer, raps me on the ankle

just hard enough to say, “Hey, I’m still here, you bastard.

Just because you read Chekhov doesn’t mean you’re

better than I am. You don’t even read Russian yet.”

On the Red Line

Riding the Metro to work,

underground through Washington

something like living a life

on the surface—beginning,

middle, end—although you don’t

know where the middle was

until you get to the end,

somewhere near which you come out

into air and light. Monuments

and rives go by. Planes fly past

overhead. And then you go down

again, into the earth. You notice

that people getting off rarely

have anything to say to people

getting on. And when you

get off, you come up not into some

blue heaven but into a huge building

with endless corridors, stairways

leading to nowhere, doors with

warnings scrawled on paper.

If you pass through here

you won’t come back.

No hardware on other side.

Door will lock.

Tectonic Platelets

Lost count how many. Bone marrow stuff.

Floating chorizo and eggs. Expressiveness

maxed out beyond cognition.

Incontinents passing like shits in the night

time of splendor. Barca rolls toasted, buttered.

Over easy. Nothing stays put. Health

Cares, stupid, never plan ahead. Heartquakes

raze, first, substandard structures.

Zeitfest

Short in several respects, long in others.

The trick? Learning to forget how to remember how

it was to step out into the town, to walk its cobbled

streets, looking into shop windows on the hauptstrasse.

Defining the horse—not unlike riding one. Pacing

first one way then another, or circling the room

as if awaiting some delivery. And all those rooms

and houses, churches and jails, built stone

upon stone upon stone.

Poems chosen by Roger Mitchell

Fountainebleau: Feeding the Carp from Winter Journey (1979, reissued 2015)

After a formal tour of the park and gardens

we visit the palace itself, traipse through the state

apartments. We look down at the pools and gardens

through upper-story windows, sprinklers playing

on the grass. And, coming down, we go out

to the carp pond, look down through the murky water

and see whole schools of them, fat and hungry,

looking up at us. A small child teases them

with cigarette butts and candy wrappers. In dismay

we offer them what we have—bits of cheese,

crusts of bread, even half an apple. They eat it all.

And, when we have nothing more to give, we walk back

through the gardens to our car and drive into the forest.

For a while we play king and court among the trees,

climbing and walking, or riding to the horns. And then,

cold and hungry, we stumble into Barbizon, village of artists

and models, and starving, but still in love,

we hang ourselves in a garret.

A Little Stream from Winter Journey (1979, reissued 2015)

I ran along the bank of a little stream.

I ran and I ran and I rand and I ran.

I sat at its edge. My feet dangled

in the water. I lay on my stomach,

writing my name on the surface of the water.

But in fact I have forgotten my name.

The stream runs along without me.

It runs and it runs and it runs.

Through meadow and forest, by boulder

and tree. Beside smoking abandoned farms

and small, dirty villages. It runs

red with blood, and the sound of screams

is lost in its idiot burble.

Clouds from Guide to the Tokyo Subway (2006)

Nuages, fetes, sirens, Hiram exclaimed,

but the greatest of these is Nuages.

Hiram stood in relation to the other philosophers of

Central City as Copernicus did to other Polish astronomers

of the fifteenth century. He revolutionized our thinking.

The reality of the world lies with its ephemera, Hiram

would say, thus aligning himself with the Japanese in their love

of fireflies, fireworks, and cherry blossoms, and with American

businessmen in their love of quick, short-term profits.

Hiram focused us on clouds rather than rocks. He tuned our

telescopes to fluffs of evanescent white, their drift across our

skies. And windy days were best. White puffs blown by on

random winds, here today and gone in just a minute.

Take Me to the Water from Guide to the Tokyo Subway (2006)

I wanted to go over to the lake, but instead he drove me inland,

starting from the driveway, where bricks were laid in a herring-

bone pattern and a sign said don’t block the cow-path,

inland to a town not far from a naval air station. I said drive me

to the lake, so that I can clamber over the piled-up, quarry-cut

rocks along the shore, so that I can watch the birds seeking fish

where the nuclear power plant lets its warmed up water flow into

the much cooler water of the lake. I said take me to the water, so

that I can watch the smudge of a steamer far out on

the lake, working its way slowly to the right along the line of

a straight, hard, sharp, direct, flat, utterly convincing horizon.

Guru from Organ Harvest with Entrance of Clones (2007)

L’Ang Po often spoke about carrying, about picking

things up and putting them down.

Each of them was talking, as part of the ceremony,

far beyond form and emptiness.

The seasons changed, the war intensified. Ice caps

were melting too quickly.

In Mexico together, we all sat down to sew,

to stich our names in the fabric of time.

Liberation, freely given to all concerned, just

something to pull about our shoulders.

Example and precept. Precept and example.

Not a ruse, but an affirmation.

Far afield, we have chanted the moon’s name,

held in abeyance by long-time donors.

Silent voices—alive and well, after all

is said and done.

Selected Fiction by Halvard Johnson

Chosen by Carole Rosenthal

Uncollected Stories (first published in HSR 4)

From songs the conversation turned to poets; the Commandant remarked that they were a bad lot and bitter drunkards, and advised me, as a friend, to give up writing verses, for such an occupation did not accord with military duties and brought one to no good.

Pushkin, "The Captain's Daughter"

I

To Lenny, Ben's story was not a new one, but Lenny, over the years had grown used to hearing the same stories in "somewhat altered versions," as was said. In the course of telling one of his stories, Ben, Lenny's friend and sometimes mentor of many years, rambled all over creation, mixing up lies and truth in a shameless manner. When he'd reached either an end or a stopping point, Ben would push himself back from the table, rise, and say, with a wink or something verging on a sneer, "Of course, that was all lies," as though anyone who expected the truth from him ought, as a legendary Hollywood figure once said of those who believe in psychoanalysis, to have his head examined.

But at the beginning Ben would say something like this:

"Let me tell you about my first wife."

Ben's first wife–his only wife with the papers to prove it–had been twenty, maybe thirty, years junior to him when he married her, and had probably put up with a lot before finally decamping. Her name, Lenny knew, was Martha. And, when Ben married her, she had no money, or any prospect of money. So, on the day she dragged her suitcase through the streets of San Luis Obispo, heading for the bus station, she wasn't worse off than when she had arrived. Older by a couple years and a tad fonder of the bottle perhaps, but no poorer, no richer.

Ben's lean, muscular arm lay stretched along the back of booth, one of his fingernails tracing the curve of a C someone had carved in the wood. Lenny thought at first it was someone's initial, carved by one hand and inked in by others over the years, but then later, when Ben, engrossed in the story he was telling, leaned forward on his flanneled elbows, Lenny saw that it wasn't an initial at all, but rather the first letter of the word CUNT.

The bar, called Harold's, stood kitty-corner from a gas station/grocery combo in one of those little crossroads towns on the plains that seemed to consist only of a bar, a grocery, and a grain elevator.

Above their heads, grimy fans turned lazily and dingy, water-stained squares of composition board still managed to soak up some of the clatter and chatter from several farmers or ranchers or garage mechanics at the two pool tables beyond the three or four tables between the booths and the door to the gents' and ladies' rooms.

Ben gazed for some moments past the backwards red-neon script of the faintly humming Coors sign, out the grubby window, and beyond his mud-encrusted, red pickup truck to where the two-lane highway lay, with its whirls of dust that kicked up when some car or truck passed by, and then turned back to Lenny, who was toying absently with the zipper of his windbreaker.

"Ever been down in Presidio, Sonny Boy?"

Lenny shook his head, his long, brown hair.

"Well, it ain't much, lemme tell you. It's pretty much due south of Marfa, down there on the Rio Grande about halfway between El Paso and the Bend. A real pisshole. But there's a nice Mexican town named Ojinaga right across the river."

His eyes drifted out the window again and across the road. Not much to see there at the moment–just some crumpled beer cans, scraps of paper, some heaped-up tumbleweed along a fence, an uncollared mutt of some kind sitting on the shoulder opposite, looking first one way and then the other. A guy in gray and white striped coveralls holding a pool cue dropped a quarter in the jukebox and some stompin' music came on. Lenny, younger and more impatient than Ben, waited for more of the familiar story. Ben, having finished his bacon cheeseburger, eyed Lenny's mostly uneaten one, and then, reaching over, scooped it off Lenny's plate and took a bite out of it that nearly finished it off. When Ben's hand then reached out for some of Lenny's fries, Lenny lightly batted it away.

"And? And?" Lenny, tuning out the country music and the pool table chatter, drummed the table nervously with his left hand.

"Well, to make a short story long, Martha was working at a greasy spoon called Sancho's there, just about the only decent place to eat in town. You know, where you could get something besides enchiladas, tacos, and beans. She'd come into town with some guy, and they were heading vaguely for the coast, but he'd just taken off one morning before she woke up, and she never heard from him again.

"So, she started waitressing at Sancho's and saving her pennies. But the pennies came slow and hard in that town, so she just had to start selling it."

"Selling what?"

Ben looked narrowly at him. "Whatever you suppose she had to sell."

Lenny blinked. A new wrinkle in the old tale.

"And?"

"And then one night I was in there. I'd been down at the Bend camping in the Chisos for a couple days, and was on my way to a teaching gig in El Paso. Martha was sitting down and chatting with me since there weren't many customers in the place, and this guy comes in–a real valley redneck type–and starts in on Martha. He's drunk, of course, so he doesn't listen to me when I tell him to back off. So, he's pawing her and breathing on her, and I grab his shoulder and pull him off. But he takes one swing at me, and I'm out like a light."

Ben scrutinized the landscape beyond the window again. The dog had vanished. A Greyhound bus lumbered past.

"Well," and here Ben leaned forward on this elbows, and Lenny saw over his shoulder the word carved in the wood behind him. "Well, when I came to I was in Martha's bed. She had a small room up over a feed store there. She was holding a cold washcloth to my jaw, and my head felt like it was about to explode. But my gut was exploding too. I must've collected something from the water down by the Bend because I was out for days in that little room. I'd wake up with the sweats, and Martha would be cooling me off with washcloths and towels and alcohol rubs. And then I'd wake up with chills, and she'd climb into bed with me to keep me warm."

Now Lenny turned to stare out the window.

"And listen to this." Ben reached out and tapped the younger man's wrist.

"While I was there, thrashing about in chills and sweats, you know what she did?"

Lenny shook his head. He wasn't sure he wanted to know.

"She phoned up the school in El Paso I was going to teach at and told them I'd been taken sick and wouldn't make the first week of classes. It was right at the beginning of September all this happened. And they told her if I didn't make the first class at the beginning of the second week to forget it. And that made her so mad she told them to take the job and stuff it. And that's just what they did.

"And what did you do?"

"Well, I was sick enough I didn't do anything for a while, but when she finally told me what she'd done all I could do was laugh."

"And then?"

"Oh, we just lived together there in Presidio for a while. It was probably nearly November before I was really over it."

"And she took care of you?"

"Yep. I'd sort of been counting on that job though. I had some money, but not much. Enough to get us to the coast. I knew some people in Cruces and Yuma, and she knew some in San Diego. That helped. You know, they fed us and let us sack out at their places until we'd decided where to go or what to do next."

"And when did you get married?"

"We got married right there in Presidio, believe it or not. In fact, that was the only way I could get her to leave town with me, even as down and out as she was."

Lenny's gaze drifted out the window, and when he turned back to Ben, the older man was smiling.

"Did you like that one, Sonny Boy?"

He took Lenny by the chin and shook it. "Well, it was lies, all lies, Sonny Boy. And don't you forget it."

They'd known each other for less than a month when Ben first regaled Lenny with a version of this story. Years later, after Ben had disappeared and all that, Lenny sat talking with one of Ben's fans, a writer from the East Coast, somewhere in Virginia maybe, who was compiling a collection of interviews of people, other writers mainly, who had known and cared for Ben and/or his work. They were sitting in Lenny's pay-by-the-week motel room on the outskirts of Pueblo, Colorado, where, after shifting piles of books and papers onto the top of the dresser, they'd pulled a rickety writing table away from the wall and placed chairs on either side of it. On the table between them were two glasses, a bottle of Kentucky straight corn whiskey, a bowl of ice cubes, and a Sanyo tape recorder–a postmodern still life.

Lenny, over the last couple years, had grown tired and wary of interviewers. In fact, he'd stopped giving interviews about Ben altogether, but Karla, for some reason or other, had urged him to talk to this one–Art Gilmore, a short, slightly overweight man with dark brown hair, who was loosening Lenny up for the formal interview. The tape recorder wasn't running yet.

"I'll just begin by asking you about how you met Ben, and we'll go on from there. Does that sound okay?"

Lenny looked up from the frayed, mustard-colored carpet near the French doors. "Fine with me."

Lenny wasn't very worried. Gilmore had seemed genuine when he promised to send a transcript of the interview for Lenny's approval. That was standing operating procedure for interviews of this sort, although in the years since Ben disappeared Lenny had been badly burned once or twice.

They heard several long, loud blasts on the horn of a diesel engine and then the clangorous passage of a long chain of boxcars moving up the long, slow incline across the highway from the motel. The noise was so loud that, for a several minutes, they just sat, watching and listening, shrugging their shoulders and smiling small smiles at each other.

Then Gilmore, when it was quieter, looked across the table at Lenny and said, "Ready?"

Lenny nodded grimly.

Gilmore leaned over the table, punched a button on this tape recorder and spoke loudly and clearly into the machine's built-in microphone: Art Gilmore interviewing Leonard Reed, Nov. 8, 1990, Carson Motel, Pueblo, Colorado.

Then he sat back, took a couple ice cubes from the bowl, dropped them into a glass and poured over them a few fingers of amber fluid from the bottle. He pushed the glass across the table to Lenny and poured another for himself. Gilmore sniffed at what he called "the corn," and then took a delicate, slow sip and cleared his throat.

Gilmore: Tell me, please, about how you met Ben.

Reed: Ben and I shared an office at UN-Reno back in the sixties. That was long before it was UN-Reno, of course. Back then that campus was the University of Nevada.

Gilmore: Right. Reno was one of Ben's first teaching jobs, wasn't it?

Reed: Yeah, well, there were a couple gigs before Reno that didn't amount to much. He told me about one in Omaha, where he was teaching at a convent, one of those orders where you weren't supposed to see the sisters, and where they weren't supposed to speak.

Gilmore: Quite a challenge.

Reed: Yeah, Ben had to teach his first class twice.

Gilmore: Twice?

Reed: Well, he got there an hour early and didn't know it. So, he did his thing and left, sort of amazed at how quiet they all were. And then the Mother Superior or someone comes running after him outside, hollering, "Mr. Garrison, Mr. Garrison, where are you going? Your class begins in five minutes."

Gilmore: Great story!

Reed: Yeah.

Lenny was thinking, Yeah, there's probably not a word of truth in it. Though, God knows, he'd heard Ben tell the story often enough. Much more elaborately, of course, and with the sort of variations in detail he'd come to expect of him. But, facing Gilmore, he was suddenly amazed that until that very moment it hadn't occurred to him that the entire story might be a lie. Ben still, it seemed, might have a trick or two up his sleeve.

Gilmore: Do you remember your first meeting?

Reed: Sure! I'd been given the number of my office, and when got there the door was open so I just walked in, and there he was. He was a long drink of water. You could tell that even when he was sitting down. He was sitting, of course, with his boots up on the desk–almost on my desktop; our desks were back to back. He was wearing a brownish-gray polyester suit, a white shirt, a perfectly horrible string necktie, and cowboy boots. He stuck out his hand and said, "Hi! I'm Ben Garrison, your lord and master. Welcome to Reno, the Biggest Little City in Storey County."

He acted as though he'd been there forever at first, but we were both new hires. He'd just made it a point to get to the office first. He took the better of the two desks, the larger one, the one with the view out the window. He'd filled most of the bookcases with his books, seen to it that he didn't have to get up to answer the phone, and so on. Typical.

Gilmore: [Chuckles] So you two hit it off right away.

Reed: Like oil and water, you might say.

Gilmore: Really, did it take long? Most of the people I've interviewed talk about how easy it was to like him.

Reed: Ben was a shit and a liar. No, I'll probably want you to take that out. But let's leave it in for now, though.

Gilmore: Okay. We can take it out later, no problem. Anything else about those early days?

Reed: Just the lord-and-master stuff, I suppose.

Gilmore: What do you mean?

Reed: Well, just that he meant it. He did seem to believe he was my lord and master. I was the poet, and he was the real writer. He didn't have much use for poetry in those early days, though he did come to try his hand at it toward the end.

I was the poet, so I got the smaller desk, the one with only a view of him and his feet. And he'd been published too. He'd had stories in a few of the littles, and even had nibbles from Esquire on a couple of things, though nothing had panned out there yet for him. I, on the other hand, had been hired on the basis on one little chapbook of poems and a master's degree plus some hours from the University of Toledo. Not even that. The guy they'd originally hired for my job had been killed in a car crash on his way over from California, and I was the only one they could find who could fill in on such short notice. Even though there were more jobs than teachers in those days. It wasn't like it is now.

Gilmore: So, he lorded it over you?

Reed: To the max. I was Sonny Boy to him, even at the end.

"Why don't we take a little break? Stretch our legs for a while."

Gilmore turned off the machine, and they both stood up.

"Good idea," Lenny replied. He was trying to figure out why this little guy from back east was touching a nerve with him, when all those other interviewers hadn't. It wasn't the questions he asked, or the way that he asked them. It wasn't anything in the way he acted.

"Anyplace decent to eat around here?"

"Well, there's a diner called Mom's down the road a bit. No guarantees though. Remember the old line? 'Never eat at a place called Mom's, never play cards with a guy named Doc, never sleep with a woman whose troubles are . . .'"

"Sounds fine to me," Gilmore said. "It's on me."

Lenny began to protest. "No, no . . ."

"I mean it's on my publisher."

"Well, that's different!"

II

What was bothering him, Lenny realized during lunch at Mom's, was that Gilmore had been sent to him by Karla. That's what he couldn't figure out. Ever since Ben's disappearance, Karla had been guarding his reputation, certainly his literary reputation, with a vengeance, never letting any but his first-rate (and perhaps some top-drawer second-rate) work see the light of day. Why would she send Gilmore to him? She knew he wouldn't lie to the man, certainly not about Ben, not to save Ben's proverbial skin, or even her own.

What Lenny hadn't mentioned to Gilmore, but what he assumed Gilmore already knew was that he and Karla had been married when the two of them arrived in Reno. In fact, they'd been married ever since their grad-school days in Toledo a few years before.

Sure enough, when the two men sat down again at the table in the motel, the question of Karla was what came up first.

Gilmore: Would you tell me, please, about you and Ben and Karla?

Reed: Surely you know all about that, don't you? I think the whole world does.

Gilmore: I'd like to hear you tell your own . . . side of it.

He almost said "version," Lenny thought.

Reed: Okay then.

Lenny thought back. After grad school, Karla and he had both worked various teaching jobs around Cleveland, but when Karla was diagnosed with emphysema her doctor told her not to spend another winter in Cleveland. So, they'd both started firing out letters to practically every school on the West Coast and in the Southwest, and just about when they had given up and resigned themselves to another Cleveland winter there was a phone call from Reno. The school couldn't hire them both, but somebody coming in to teach poetry writing had been killed in a car crash and could Lenny take the job? No guarantees about a second year, of course, but there'd be two full terms (with benefits), maybe something during the next summer, and a good chance of having his contract renewed.

So, with Karla jumping up and down beside him, her blonde ponytail flying up and down, Lenny had said, "When would I have to be there?"

"We start classes on September 9. If you get here a couple days early, we can get all the paperwork done and help you find someplace to live, maybe in faculty housing."

A week later they were on the road, their black VW beetle pulling a rented trailer that held everything they owned. Their black Lab named Grendel was in the back seat, running back and forth from one side of the car to the other.

The road? US 6, naturally. What other road for two writers, the image of Jack Kerouac burned in their brains, standing for hours in the rain near the Bear Mountain Bridge in New York, dreaming of a ride that would take him all the way to California on US 6. Of course, Kerouac had wanted to do US 6 all the way west, but never got farther than the Bear Mountain Bridge and so took a bus down into New York City and started again from there. And US 6 wouldn't get Lenny and Karla all the way to Reno, but it would get them well into Nevada before they'd have to take US 50 over to Reno. Close enough, they thought.

Gilmore: So you arrived in Reno, and Ben pulled his lord-and-master routine. What next?

Reed: That first term was a killer. I was doing a poetry writing class and about four sections of comp. The bastards hadn't told me about those. And Karla was going crazy from nothing to do. Reno wasn't Cleveland, by a long shot, or even Toledo, and it wasn't much warmer as it turned out. It was drier, though, and that helped with her breathing. But Karla was bored as hell. And the faculty wives . . . well, enough said.

Ben was soon bored too, and started drinking pretty heavily. I don't know if that was the beginning of his drinking problem or just a new chapter of it. Probably the latter.

Gilmore: From what I hear it might have been the beginning, though some of his problem might have been genetic.

Reed: Anyway, he started drinking a lot, and his being lord and master and all didn't stop him from coming around at all hours. Luckily, at first, there were a number of people he'd drink with. But when he started coming around at four or five in the morning on some sort of crying jag, doors began to get slammed in his face, and he ended up doing most of his crying with Karla and me.

Gilmore: That must have been rough.

Reed: Well, I would have slammed the door too, but Karla wouldn't let me. She sort of adopted him, took him on as a project, I guess. I tried to talk her out of it, said I had to work, needed sleep. She said, "Go get your sleep. I'll sit up with him," And she did–couple, three nights a week sometimes.

Gilmore: He was writing some of those great early stories that winter, wasn't he? You know, "The German Problem," "Small Changes"–stuff like that.

Reed: Yes, those are two of my favorites. But God knows when he had time to write them. He was doing as much comp as I was, and he didn't slack off on the papers either. I saw some of them, just covered with notes and suggestions, little arrows running here and there.

He never did a public reading there in Reno. Not in those days anyway, though he maybe did later.

Gilmore: At least three that I know of. In fact, I was at the last one in '87. He read "Small Changes" too, and they loved it.

Reed: Uh-huh, they would love it now, but they wouldn't have loved it then. You can be sure of that.

Gilmore: You mean because of his send-up of that dean? What was his name?

Reed: You got it. His name was . . . I forget now too. Same guy that told me I was being hired to replace a corpse.

Gilmore: What did he cry about?

Reed: Oh, it could have been anything. Sometimes it was Martha. Sometimes it was his parents. Sometimes it was somebody he knew in the service–you know, in Korea. Sometimes it was just the sad state of the world.

Gilmore: You never knew Martha?

Reed: No, but I heard enough about her from Ben, and later from Karla, who met her once or twice. Most of the stories Ben told me about her were probably lies. That's just the way he was. Ben told me they'd met in Texas somewhere, but Karla later learned for a fact that they'd met each other someplace in California–San Luis Obispo maybe, or Chico. I don't know.

Gilmore: Tell me more about that first year in Reno.

Reed: Well, it was more of the same, mostly. Ben went off somewhere during the Christmas break. We never knew where. But, to our surprise really, he was back for the start of the spring term.

The drinking began again though and got worse rapidly. He didn't make it to spring vacation. When he started missing classes, they just fired him on the spot and kicked him out of faculty housing.

Gilmore: He did have a contract, didn't he?

Reed: Yes, but they paid him off for the rest of the term, and on top of that they gave Karla one class to finish up and divvied up the rest among the four of us who were already teaching comp.

Gilmore: Quite a load.

Reed: Yes, but all of us thought it was worth it to be rid of him.

Gilmore: Still not friends?

Reed: No, not then.

Gilmore: When did things begin to change?

Reed: Well, it wasn't until that summer.

Lenny relaxed a bit, took a sip of corn whiskey. That was the summer Ben showed up at the door of their house in a brand-new pickup truck. God knew where he'd gotten the money or the credit to buy it, but somehow he had. And Lenny and Karla had just about resigned themselves to a hot, dusty summer in Reno with no courses to teach, no money to spend, and no car to run around in. Their VW had just about killed itself pulling that trailer two-thirds of the way cross the country, and didn't make it much past winter.

So, Ben showed up, and Karla ran out and flung her arms around his neck. Even Lenny was delighted to see him. And, better yet, he was entirely sober. Lenny kept a wary eye on him, but there were no bottles hidden away in his suitcase. After the first night, Ben checked into a nearby motel and they didn't see much of him for a few days. But then he showed up again, beaming. "Well, it's finished. But I don't have a title for it." He held up a sheaf of stories. "This is it," he exclaimed. "The first book."

Karla grabbed the MS out of his hand and flipped through it. Many of the stories there were entirely new, but some were ones she knew. "How about 'Houselights'?" she suggested.

Ben, after a moment's thought said, "Yes, indeed. That should do it."

III

Gilmore: When did you know that he'd come back for Karla?

Lenny reached over and turned off the machine. "You're the interviewer from hell, aren't you?" He stood up and walked away from the table.

"Calling it quits?" Gilmore asked, without getting up.

Lenny thought for a moment, tempted. But then he said, "No, but let's call it a day. You got someplace to stay around here?"

"I'm right across the way there–number 15." And Gilmore gathered up his bottle and his tape recorder and left.

The summer in question was one of the best/worst in Lenny's life, one during which he acquired a friend who made enemies seem superfluous, and lost a wife to him–at least for a while. Lenny never knew for sure whether anything had happened between Ben and Karla during those first school semesters in Reno, but there was, he remembered, some point during their travels together that summer at which he knew clearly that Karla was, for the first time, more with Ben than with him.

Crammed into Ben's red pickup, the two men shared the driving, and Karla functioned as navigator and tour guide as they explored the Wild West. They began with short excursions out of Reno–over to Tahoe City on the California side of the lake, north to Pyramid Lake and the Indian reservation there, southeast to Hawthorne and the Excelsior Mountains. They explored little towns like Fallon and Wadsworth and Lovelock. When the excursions grew longer, they bought sleeping bags and a tarp and would, weather permitting, just stretch themselves out under the stars at night. They'd eat out of stores, or at truck stops or small dusty restaurants along the highway. The three of them would wrangle for hours about stories and poems and writers. Ben thought that Lenny should stop writing poetry and get into fiction "where the action is." And Lenny would nod, as though he agreed.

"Nobody reads that stuff anymore," Ben would say, and Lenny would nod and smile, this time in genuine agreement. But he'd keep on scribbling on a steno pad he always carried around with him, and he would occasionally show them something.

When he did, Karla, who'd never liked poets or poetry much until meeting Lenny, and still did not by and large, would be surprised that she didn't dislike it more than she did, and Ben–well, Ben would just scratch his neck and shake his head.

Since Ben's enforced departure from Reno, he'd taken to wearing blue jeans and plaid shirts, along with a leather cowboy hat he'd picked up somewhere.

"I just don't get it," Ben would say, "–why a talented guy like you would spend his life nibbling around the foothills when there are peaks out there to climb."

"You're mixing your metaphors, Ben," said Lenny, annoyed suddenly at the folksy westernisms of this guy who'd been west of the Mississippi barely longer than he himself had.

"Oh, fuck my metaphors. Why don't you just listen for a change?"

"Take it easy, Ben," said Karla, the Peacekeeper.

"Butt out," said Ben, annoyed with Karla now.

And Karla would sit there looking glum while the two of them clubbed each other over the head with theories, debating points, and so on, until they were both so exhausted they could hardly see or talk straight.

The story, Ben argued, was where the real world hit the page, where real people reached down into themselves and dragged up the tattered remnants of their souls for all to see. Lenny had no argument with that, but would claim that the poem was way out in front, out where language gave birth to itself.

"Fuck that," Ben said, reaching for Karla's crotch. "This is real. You're just jerking off."

Gilmore: Was that when you knew?

Reed: No, Karla just laughed and swatted his hand away. But there was something in the way she did it, something that told me she didn't really mind being Ben's touchstone of reality.

Gilmore: And when did the actual breakup occur?

Reed: Oh, a week or two later. We'd been back in Reno for a couple days, and she just came into my study one morning and said, "Lenny, I'm going with Ben for a while."

I said, "What?"

And she said, "I'm going away with Ben for a while."

Gilmore: And they left? Just like that?

Reed: Just like that.

Gilmore: You know Ben's story called "Saturday"?

Reed: Of course.

Gilmore: Would you give me your thoughts about that?

Reed: You're a real asshole, you know? The guy steals my wife and then writes a story about it from my point of view. What do you think I think about that?

Gilmore: Just thought I'd ask.

IV

There's a story by Ben Garrison called "Lacrymosa" that is about two men and a woman who go camping together in the Mogollon Mountains, just west of the Gila Wilderness in southwestern New Mexico. The area is a wild one, and they've been traveling on old logging roads for three or four days, and they haven't seen other human beings but themselves. The story is told from the woman's point of view.

In the story, they've been traveling together all summer, and the woman is painfully conscious of being in the process of leaving the younger man for the older one. The older man, whose name is David, has been prodding her in this direction for some time now. The younger man, whose name is Les, is not quite aware of what's going on yet.

The climax of the story occurs on one of those cold mountain nights that can come even in mid- or late summer in those desert mountains.We came down off the mountain to a flat, grassy place near the bank of a stream. It was nearly dark when we stopped and began to set up camp. I'd swear the temperature dropped twenty degrees the minute the sun dropped behind the mountain.

Les and Dave put up the tent, while I started gathering wood for a fire.

"Let's get all the deadwood we can find before it gets any darker, and we'll make us a big one tonight, one that'll last all night long."

I began to drag branches and brush and stuff into the center of the clearing, near where the tent was going up, and when Dave and Les had all the pegs hammered in they joined in the collecting of firewood.

First, we made a small fire just for cooking, and after we'd eaten our beans and corn we started piling on heavier stuff. Sparks and smoke flew up to the treetops and disappeared into blackness. The guys were jubilant, excited by the roar of the blaze. Somehow that day I'd made a decision. I wasn't sure when or how.

Dave shouted to Les across the crackling fire, "Let's throw on everything we can lay our hands on. It might really last all night then."

The fire they made was so big, so hot we couldn't get within ten feet of it at first. So we stood back away, stamping our feet, and blowing into our hands–hot and cold at the same time.

I let the guys take the tent, and laid my bag on a tarp on the ground outside, where I could watch and be warmed by the fire. High above the fire were sparks mixed with stars.

I thought about Les, and I thought about David, and then I slept.

During the night, I awoke every so often to see, each time, the fire growing smaller, weaker, less bright. In the early morning, an hour or so before dawn, I heard, far off, a woman crying–great wrenching sobs that seemed to be coming closer.

At breakfast, David said, "Did you hear that mountain lion last night?" Les hadn't heard it, but I said yes, as though I'd known what it was. And to me it was still a woman crying–for Lester, for David, for all of us.

V

Before leaving Pueblo the next morning, Gilmore promised he'd send Lenny a transcript of his interview with Martha Landridge as soon as she'd okayed it, which, Gilmore thought, should be a matter of days. But it turned out to be more a matter of months. In the meanwhile, Lenny finished up the workshops he was teaching in Pueblo and moved on to another gig. Karla had exploded, of course, when she learned of the Landridge interview, just as Lenny had thought she would. In fact, she'd reneged on her many commitments to and agreements with Gilmore, and absolutely refused to let him use the interview he'd done with her as long as he went ahead with his plan to use the one with Martha.

Karla also tried and failed to pressure Lenny into withdrawing from Gilmore's project. Lenny stood firm. "Why the fuck did you send him to me if you didn't want me to talk to him? This doesn't make any sense, Karla. What difference does it make whether he talked to Martha or not?"

"Well, if you don't understand, Lenny, I'm just not going to explain it to you." And then she hung up.

"Women," Lenny muttered to himself as he fixed another drink.

At the time of Ben's disappearance, Lenny and Karla had indeed intended to remarry, but time and events worked against that. A document turned up among Ben's papers that made Karla the legal executor of his estate, which involved a considerable amount of money Ben had made during those last couple years. She was fairly well off. And very, very busy.

But they stayed in touch by telephone, and Lenny supported her in every way he could, though he wouldn't let her push him around.

When the transcript caught up with him, Lenny was halfway through the spring term in Fort Collins, Colorado–living at a motel, as usual, and–not as usual–involved with a redhead in his senior poetry workshop who had managed, much to his amazement, to revive his interest both in sonnets and in sex.

The transcript arrived in a hefty manila envelope with Gilmore, 56 Ransome Road, Roanoke, Virginia, in the top left-hand corner. Lenny tossed it onto a pile of papers on the chest of drawers and let it lie there for a couple days while he waited for a good time to read it, but then a newspaper got tossed on top of it, and then something else, and between sex and classes and some pretty heavy drinking, it might have disappeared entirely if one night Sharon, the redhead, naked and damp and pink from the shower hadn't idly started looking through the heap on the dresser.

"What's this, Len?" she asked, waggling the envelope at him.

Lenny, half-drunk and sleepy from sex, narrowed his eyes, tried to focus. Finally succeeding, he saw the name Gilmore.

"Oh, that's the interview with Martha."

"Who's Martha?" asked Sharon.

"Nobody you'd know," said Lenny, immediately regretting the tone.

"Come on, Len. Who is she? Some old flame of yours?" She'd seemed to ignore the tone in Lenny's voice.

"Not a girlfriend, no. Just a friend of a friend. A former wife of a former friend, actually."

"Who's the friend?"

"Ben Garrison," Lenny replied. "Know his stuff?"

"You knew Ben Garrison?" Lenny wondered for a moment if she was putting him down. But Sharon seemed simply delighted. "I think I've read everything he ever wrote."

"Not everything," Lenny said. "Not everything he wrote has been published."

But Sharon didn't hear him. She was away in memory land. And when she returned she said, "He read here in Fort Collins back when I was a freshman. He read that story called 'Houselights.' Do you know it?"

"That was one of the great ones." Lenny found her slipping out of focus.

"Yes, he read that and some poems, but the story was the thing."

"That's what he was good at. Did you sleep with him?"

Sharon smacked Lenny's naked rump with the flat of her hand.

"Can I read it?"

"What, the interview?"

"What do you think?"

Her finger was already into the envelope, tearing the flap away and destroying the entire envelope in the process of opening it.

"Well, why not? Why don't you read it out loud?"

Lenny poured himself a bourbon and dropped an ice cube in it.

"Want a drinkie?"

No, thanks. I'm going to have to drive, looks like."

So, they settled back on the bed, and she began.

"There's a letter here. Want me to read it to you?"

"Sure. Go ahead."

"It says, 'Dear Lenny, Sorry to be so long in getting this to you, but Martha took longer with it than I expected. It's still a bit rough around the edges, but she finally approved the gist of it.

"'As you probably know by now, Karla's pulled out of the Garrison project. When she heard that I was going to use Martha's interview, she just called it quits. I reminded her of her agreements with me, but that didn't do a bit of good. She just refuses to have her interview appear in the same book with Martha's. And I, of course, couldn't back down. The Martha material is important, as you'll see.

"'Quite frankly, I don't know what Karla's problem is. If you have any idea, maybe you'd let me know. I doubt, though, that Karla will change her mind. She seemed quite adamant.

"'Thanks for your cooperation on this, by the way. The book will be much better because of it.

"'Keep in touch. Yours, Artie Gilmore.'"

Sharon looked over at Lenny, who was slowly shaking his head from side to side. He held out his glass, and she reached for the fifth of Jack Daniels on the nightstand. She poured him a drink and then passed him the bottle. "Here, put it on your side."

"Oh, my. Oh, my," Lenny said, mournfully.

Sharon stretched herself out on the bed, her body returned from pink to freckled white. Next to her, Lenny felt tan. She fluffed up the pillows behind her head and began once more to read. Lenny watched her for a while, saw how the fingers of her right hand, the hand not holding the transcript, continually ran up and down her body, over her breasts and rib cage and stomach to the mound at the top of her thighs, where they twisted themselves into curly red hair, even redder than the hair on her head. But after a while, he rolled over on his back and stared up at the ceiling.

Art Gilmore interviewing Martha Landridge, October 15, 1990, Cielo Vista Hotel, Owensburg, California.

For several months, Martha Landridge refused all my requests for an interview. Our conversations would be by telephone, and they were invariably short. I'd give her reasons, and she'd refuse. She never talked publicly about Ben Garrison. That was it. She said.

Then, just as I was about to give up hope of ever putting questions to her, I met, just by chance, a Los Angeles painter who'd known her during the two or three years she lived in LA back in the early eighties. The painter offered to intercede with Martha, and the result was that Martha agreed to meet me for half an hour at the Cielo Vista Hotel in Owensburg, California. I promised, as is customary, that she'd get to check out the transcript of the interview and make corrections and changes. I also promised her that no photographs of her, from whatever source, would appear in the book or in any publicity for the book.

So, that's how things stood. Our conversation on October 15, as you will see, ran considerably longer than half an hour.

Gilmore: Do you remember the first time you saw Ben Garrison?

Landridge: As though it were yesterday. I was thirteen going on fourteen, and he was about a year older. We lived in Schenectady, New York, and were both going to the same high school, and one fall day he just started to chat after school and wound up walking me all the way home.

Gilmore: You know, people have told me over and over that Ben was twenty years older than you.

Landridge: Well, that's just nonsense. We were about a year apart; he was a sophomore when we met, and I was a freshman.

Gilmore: Why would Ben lie about that? And what about Presidio?

Landridge: Well, that's just the way Ben was. He'd bend the truth a bit, to serve his own purposes, or often just for fun. And Presidio?

Gilmore: Yes. According to Ben, you were waiting tables there, and he got in a fight over you, got knocked out by some redneck, and wound up being nursed back to health by you.

Landridge: Right. And I climbed into bed with him, to keep him warm when he had the chills, right?

Gilmore: That's what I was told.

Landridge: Have you ever read Tolstoy? "Master and Man"? Well, two men in that story, a Russian nobleman and his servant, get caught in a raging blizzard, and the servant uses the heat from his very own body to keep his master alive through the night. And have you read Hemingway? A Farewell to Arms? Remember Lieutenant Henry and Catherine, his nurse? Well, there you are–two of his favorite stories when he was in high school.

And you know what else? He told that Presidio story of his to some writer from Chicago, who used it himself, only in his version it's a sixty-year-old man climbing into bed with his eighty-year-old father to keep the old man from pulling the tubing out of his arms so that he can die.

[Laughs] Ben never let go of a good story, and he didn't mind spreading good stories around either. Never got mad when somebody cribbed something of his.

Back in the sixties, know what he'd do? He'd take one basic story, dress it up in various ways, and send it out to six or seven magazines all under different names. He loved to do that. Do you remember "In the Thicket"?

Gilmore: Of course.

Landridge: That was in Houselights, his first collection back in '65 or so. Remember?

Gilmore: Yes, I do. It was a fine story.

Landridge: Well, "In the Thicket" must have been in about twelve different magazines, and some of them biggies too. You know, The Paris Review and such like. He used to call "In the Thicket" his All-time Champion (capital A, capital C). Later, I think he played the same game, but stopped keeping score.

Gilmore: When did you and Ben get married?

Landridge: March 10, 1962, in Westminster, Maryland. He'd been off to college and even out of college for two years before we ran into each other again.

Gilmore: What were you doing during those years?

Landridge: Me? Oh, this and that. Mostly working as a dorm counselor in a private girls' school in Virginia.

Gilmore: And how did you and Ben get together again?

Landridge: Would you believe, he came to that school on a teaching gig. There's a short, four-week term they squeeze in there between the fall and spring terms, and he'd been hired to replace some Israeli writer who'd canceled out at the last minute because he needed a prostate operation. Ben was hired to teach poetry writing. Can you imagine? They must have been desperate. [Laughs]

Gilmore: Well, poetry wasn't his strong suit back in those days, was it?

Landridge: You know, he thought it was.

Gilmore: No, did he?

Landridge: I think he found poetry easier at the time. He was antsy in those days, and didn't like to commit the large blocks of time that fiction writing demanded. Poetry he could toss off and come back to whenever he had time or was is the mood. He told me once about writing a poem at the same time that he was hectoring a freshman comp class about comma splices or some such thing. I mean, literally writing it out while he was talking about something else.

Well, I did my best to talk him out of it.

Gilmore: Out of what?

Landridge: Out of writing poetry! I really hated poetry (and poets too) in those days. Couldn't stand the stuff. It was all so prissy and precious and yucky. And the poets! All that too-sensitive-for-this-world stuff–I really hated it.

Gilmore: And now?

Landridge: [Laughs] Well. I've found one or two I can stomach, believe it or not. In fact, I've been living with a poet for the last couple years. [Laughs again] Maybe I'm just going dippy in my old age.

But, more seriously, one reason I wanted him to stop writing poetry was that poetry writing left him with too much time on his hands. And I figured that if we were going to make it together he'd have to cut down the amount of time he had available for drinking and womanizing.

Gilmore: Did it work?

Landridge: You know the answer to that one. It did for a while, long enough for him to crank out some really good work. But when he started making money at it, the money started buying him time, and we were back at square one. I went through two or three cycles of that with him and then I got off the merry-go-round.

Gilmore: That was in '74, when you got divorced in Vegas.

Landridge: Well, Vegas was where we split up, but we never did get divorced.

Gilmore: Come on, I don't believe it! Divorces are a matter of public record.

Landridge: Have you ever checked it?

Gilmore: No, but I could easily enough.

Landridge: Go right ahead, my friend. But you'd be wasting your time.

Gilmore: You could have been divorced anywhere.

Landridge: Then you'd be wasting even more time, wouldn't you? Why don't you just take my word for it? Why would I lie?

Gilmore: Why would he lie? About that?

Landridge: Just for the fun of it, most likely.

Gilmore: That means that . . . Do Karla and Lenny know?

Landridge: I seriously doubt it. They will, though, when this comes out. Won't that be fun? Gilmore: But if you're still legally married to him, what about the money, and his "literary remains" so to speak?

Landridge: Oh, pish, Artie–I've never needed Ben's money, and Karla's doing just fine with his remains. She'll hold the banner high, if anyone will.

Gilmore: What about "Night Life in the Desert"?

Landridge: Did Karla show you that? It's never been published, you know.

Gilmore: It's coming out in Esquire next month.

Landridge: Wouldn't you know. Well, more power to her. Anyway, the gist of the story is true, but not the part about the divorce. And did Karla tell you about the title of that story?

Gilmore: No.

Landridge: Well, the original title was "Flamingo." Ben talked the manager of the Flamingo Hotel down in St. Pete into paying him about five hundred dollars to use the name of the hotel in the title of his story. Can you believe that? And then, just before the story was published, Ben changed his mind, and for years afterwards he joked that the hotel had probably put a hit man on his trail. [Laughs]

Sharon laughed to herself and began to ask Lenny if he thought that might be true, but Lenny, she saw, was asleep, even snoring lightly.

She kissed him lightly on the forehead and climbed out of bed. Gathering up her clothes from here and there on the furniture and floor, she went in the bathroom and dressed. She used the toilet, washed her hands in the washbasin, finger-combed her long red hair at the mirror, and then back out to the bed, where Lenny was still asleep, his thin, graying hair disheveled, his mouth wide open, a slender trail of drool making its way down from the corner of his mouth.

The transcript of the interview lay on the bed where she'd left it. Sharon picked it up and began to read again, but not aloud anymore. Then she, glancing at her watch, she tossed the transcript onto the dresser where she had first found it, and went out to her car, a sporty red number with Colorado plates that said "2 SWIFT."

She turned the ignition key and sat quietly staring off into the darkness for a minute or two, the engine purring softly. Then she hopped out of the car, slipped quietly back into Lenny's room, took the transcript from the dresser and went out again, pulling the door quietly shut behind her. With the transcript beside her on the empty bucket seat, she drove off into the night, already excited at the thought of reading it alone–at home, in her own bed.

My Father's Novel

(Published in HSR 36)

Chapter One

At first I saw the guy in cargo shorts and green t-shirt only from a distance. Even so, I recognized him as the fellow who'd stolen my father's orange VW camper and parked it in the lot down by the monastery. Not that my father was any sort of monk, or even a regular visitor to the monastery. The monks, though, were lenient about his use of their parking lot, since none of them owned cars, and visitors were infrequent.

It was in that van that I had found the MS of my father's novel, among all sorts of memorabilia and other detritus he had amassed over his lifetime. The novel, when I first found it, held together only by rubber bands and a large paperclip, was a total surprise. I'd never known that my father had a novel in him, struggling to get out.

Struggling, yes. And unfinished too. Every page had "unfinished" written all over it. And yet many, many pages had "genius" scribbled on them too, pawprints of my father's favorite Xolo dog.

Chapter Two

The first chapter of my father's novel found him trying hard to find a beginning, and what resulted was a sort of in medias res sort of thing, echoing the voice of a son he couldn't have known well at the time he disappeared from our lives, my mother's, my brothers', and mine. As is so often the case with children who grow up without knowing one or both of their parents, the missing parent (or parents) seem to appear from time to time during their lives, but only in glimpses and flashes.

I knew that guy in shorts and green t-shirt, though I never knew his name, and, after a time, came to think of and refer to him as GT--green for the color of his t-shirt and tan for the color of his shorts (maybe B for beige would have been better, but GT it was). GT used to hang around with a young lady some of us called Ith (after Ithaca, where she'd gone to college) and some of us called Philly (because somebody once said she sounded just like someone from Philadelphia).

Chapter Three

My father slipping out through a half-open door -- a recurrent image during most of my young life. No slamming of doors, just a sudden absence of indeterminate length, sometimes a week or a month, sometimes a year or longer, until he was gone forever, leaving behind little more than his unfinished novel. His absences seemed not to bother my mother or my brothers (both younger than I). His various returns went almost unnoticed by all of us.

Chapter Four

Let me tell you now, before we're too far along, my father was no novelist. He never even claimed to feel he had a book somewhere inside him, let alone a novel or slim volume of verse. He did, however, have a working title that was a real killer: The Double Wife.

Chapter Five

Few of my father's chapters had titles, but one had this title: Dead of the Day. In it, he describes (description not usually his forte) a man standing at an easel (he often said "weasel") painting another man standing at another easel (or weasel) painting a man standing at another weasel (or easel), painting . . . well, you get the idea. Infinite regress, I think it's called. The painter (the primary one, who's slightly varied as the images regress) is not my father, nor anyone else I remember. No one, male or female, in our family ever got much further into the art world than kindergarten fingerpainting.

Chapter Six: Dead of the Day

The painter (as my father called him), in a green t-shirt and cargo shorts, seemed younger and fitter than the man he was painting (also in t-shirt and shorts), and beyond that second figure the painters grew smaller and smaller, but also older and older, and more and more formally dressed, as they shrank to some mere point off in the distance. All of this was somewhat blurred, so that even if you could think you were seeing an identifiable figure you probably weren't.

Chapter Seven

The cargo shorts, the monastery, the VW camper--all motifs that recurred over and over in my father's novel, giving it, I must say, a verve and rhythm that surprised me, coming from a man who, to me at least, was famous mainly for his long afternoon naps, snoring loudly on the livingroom couch.

Chapter Eight

After studying the painter (as my father was wont to call him), one notices (my father wrote) the blurred-out figure of a dark, poodle-sized dog at the painter's feet, in motion it seemed, half in, half out of the frame.

Chapter Nine: The Double Wife

My father's novel ends with a chapter called The Double Wife, which features another painter, a woman this time referred to as Ith. She stands before a canvas divided into many squares so small that a viewer must lean forward to see them clearly. But they are clear, though small, each an image of a woman in the posture we know as that of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Some hold babies in their arms, others do not. They differ also in age and size and dress. Some are naked, even some of the elderly ones. On a wall beyond the painting on the easel one finally notices a painting of the painter, her arm reaching out, brush in hand, toward her as yet unfinished canvas.

Halvard Johnson by Halvard Johnson

1. My Poetry

The only thing there is to say about my poems is

that they are never blurry! I've always written poems,

even when I was a kid in knickers. Poetry fascinates me

and, in addition, lets me almost live the way I want to

live. I don't consider myself a bard of the consumer society,

but I work in a capitalistic system. I don't claim to produce

art either. I've never worked on commission and I'll keep

on with that. With one slight difference: over the last

40 years I've always worked for colleges or universities,

but soon I'll be free to write poems and not teach for a

living. That way there's no line between my personal work

and what I do for a living. I don't stash my poems away in

drawers under the socks. On the contrary, I try to show

them to anyone and everyone the whole world over. All I

can say is that I have full control over my work. I call

it making the system work for you. The people who use me

have more money than I'll ever see. They are rich--they

are public and private institutions, successful magazines

and journals. I don't feel sorry for them. But I also work

for free--or more or less for free--most of the time. And

it's just as much fun. I can do poems for magazines put

out by young people who don't have enough money to pay the

people who work for them. If they're doing something I

think is interesting, and if I think I can help them out,

then I do it for nothing.

2. My Training

I do a lot of portrait poems which, like my love poems

stem from fashion poetry, since I've always been a fashion poet.

In the beginning, I wanted to be a full professor and travel

around the world, but it didn't work out that way. When I was

18, I was in Singapore and flat broke. The Singapore Straight

Times--it's still being published--offered me a job as a poet.

I had a beat-up Smith-Corona, but every time there was something

to write a poem about, I got there too late. After two weeks they

fired me, and for a long time I didn't have any money. My inspiration

also comes partly from news poems. I really admire newspaper poets.

In my opinion, news is an exciting field for a poet. I've studied

the work of the papparazzi poets very closely. For me, their poems

are very powerful. I think that poetry has been made too intellectual.

Especially by beginners, or those who study poetry but don't dare

push the button.

3. The Subject

Q: As a poet, you are an anti-formalist. Your reaction

to fine arts implies that poetry must, first and foremost, be

the uniqueness of a look at a subject and not only at the form

in which the subject is arranged.

A: Absolutely. The subject--that's the big question.

That's what I'm interested in.

Q: How do you work up a poem?

A: It's a long process. Something no one knows about

is that I do all of my work in crayon first. I always carry

around a little notebook in which I can jot down the minutest

details concerning poems that I'll write some other time. I

can't type. So I scribble down handwritten notes on props,

lighting, the compositional parts of my poem. Perspiration

under the arms, puffed-up lips, a kiss, a man's shoulder, a

woman's hand, the inside of the elbow, the interplay of muscles,

of vowels and consonants, a man and woman naked to the waist,

a man.

4. The Message

There is no message in my poems. They are quite simple

and don't need any explanation. If by chance they seem a little

complex or if you need a while to understand them, it's simply

because they are full of details and that a lot of things are

happening. But usually they are very simple.

5. Drafting a Poem

It's the drafting I'm interested in. I also enjoy writing

at night, for the simple reason that people can see through my window

that I am writing. To be seen: I'm fascinated by that. Every poet

has his obsession, and that's mine. I'm used to using everything

around me. When I write a poem about diamonds, for example--and

I like writing about them on a beach in sunlight--I always have

trouble with the insurance companies. They don't want you to take

a step without a bodyguard. When I look at these poems, the hardest

part was conveying the notion that these men were armed. The woman,

the diamonds--they were easy. But I didn't want the bodyguards to

notice that they were being put in the poem. Like a lot of poets,

I am also fascinated by store-window mannequins. I like to lead the

reader on a wild goose chase. Often the women in my poems seem like

mannequins and the mannequins seem like humans. The mix-up amuses

me, and I like to play on that ambiguity in my poems. Another one

of my obsessions is swimming pools. When I was a boy, I competed

in sports a lot. I love water, it fascinates me like swimming pools

fascinate me, especially the ones in big cities.

6. A Special World

The world I write poems about is very particular: there

are always, or almost always, the same kind of characters. There

are always women, women who are apparently rich. I write poems

about the upper class because I'm well acquainted with it. And

when someone asks me why I never show the other side of the coin,

I reply that I don't really know much about it, but that there

are other poets who can do a marvelous job. I prefer to stick to

what I know. If I wrote a poem about women in a poverty-stricken

setting, it would be completely false. People have said that my

poems have nothing at all to do with reality. That's not true:

everything is based on reality.

7. Women

I don't work very much in my study because I think that

a woman I'm writing about cannot come to life in front of a wall

of books. I want to write about how a woman of a certain milieu

lives, the kind of car she drives, her setting, what kind of men

she sees. It doesn't matter where they come from--New York, Paris,

Nice, Monte Carlo. Their nationality doesn't matter either. The

women of a certain milieu, no matter where they're from, all look