T H E H A M I L T O N S T O N E R E V I E W

Issue # 23 Winter 2011

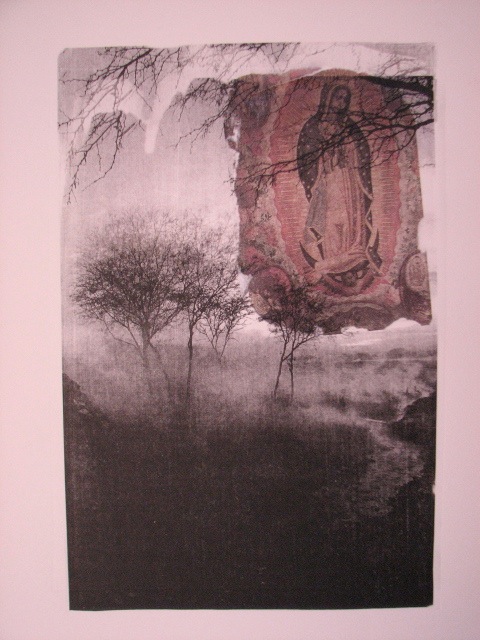

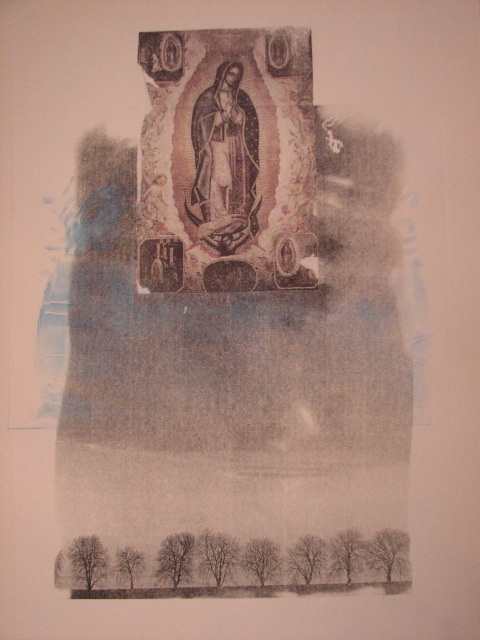

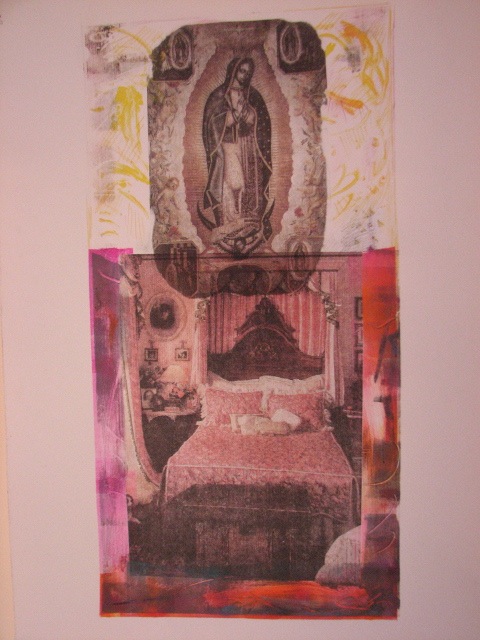

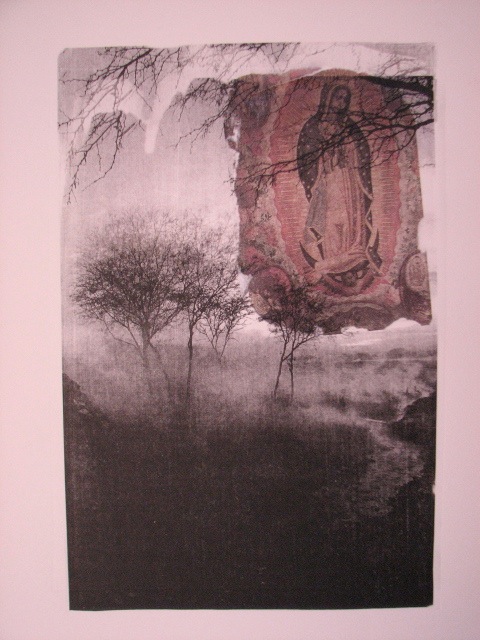

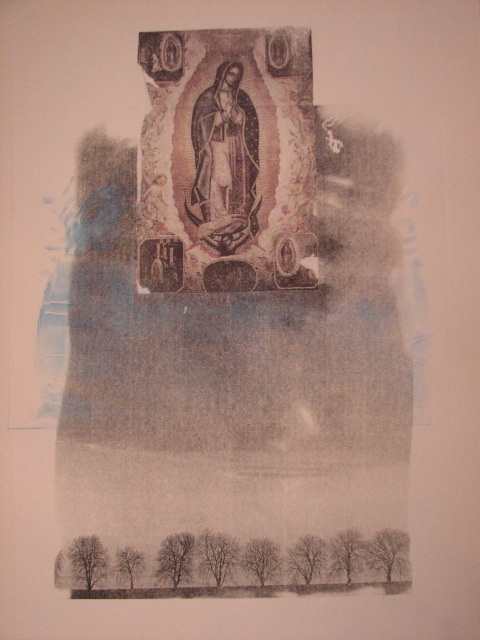

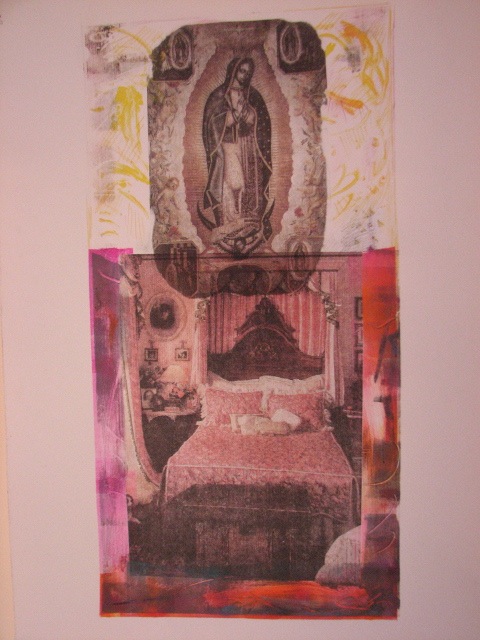

Virgens de Guadalupe by Lynda Schor

Hamilton Stone Review #23

Poetry

Roger Mitchell, Poetry Editor

Witness Tree

I walk a shaky cyprus bridge and feel cool

night air, moonlight near the casino

with fretless guitar glowing orange

over the river in national jive.

You can see white specks and float

for seconds. Where men have been hanged

cottonwoods touch themselves in moonlight.

shuck down, dive in. What is it to witness,

to walk into a voice self-assured

lost in a cloud of gnats, to go

where music goes, speak shame.

Someone or -thing is motioning. Come on in.

No, not this time.

I've sat in a place where people nod

after hearing sentiment so true

it's too true. You have too.

Just follow the sight and sound

as summer chill rises from the swamp.

To find the witness tree, walk a half mile north

from the highway. Surveyors

spiked a beginning where fighting cocks

adjust their spurs. Deer go nuts

and herd in hundreds. Mhoon Lake

sends a semi-quaver up past slots.

Come back. It starts at ankle level.

Something calls and calls

No thanks, sweetie, not this time.

Taking off, Landing

Walk into the hospital, take the long hall

past crayon drawings by school kids,

ask someone where it is, the room

with the mother, her mouth open,

her eyes half shut, her dry wind seeping,

her life leaving as she sleeps. Pray

she sleeps -- if she leaves her body,

her tuft of white hair.

Ecclesiastes says for everything a season.

A time to lift one foot then another,

a time to sit in an airplane and note

the clouds streaming underfoot,

red ants in transport, planet agleam,

commerce. . . and now it's reappearing.

All the young stricken marriages fall down,

get back up, stay with aunts

and uncles, listen to fights on the radio,

walk the red brick streets,

hear on yellow days the voice

of Nat King Cole, so silky

like a raiment of the air. Do I believe?

Yes I do. Do I doubt? Yes oh yes.

The people look out of the plane.

Their faces like little zeros.

They float over Pontchartrain, they smooth

their hands imaginatively over alligators,

who yawn for hours simply because

they forgot what they were doing.

Would you like a Dr. Pepper? Some

pretzels or peanuts? Because this

will be a long trip. Those lands and waters

tipping under the wing just that.

That bank building you left sticking up

like a tulip in downtown night

keeps changing colors, and the big clock

leaking a point of view ticks money.

When you move through space in a room

with so many lives the sun and moon

advance on the chromium content, a storm

dissolves in the west, an angel reaches

toward you but nobody sees – they see

their own significant setting, they see

what everybody sees, a willingness

to land, a ready disbelief stumbling forward.

Biopsy

Sometimes beauty comes with bad news—

voices floating far downhill, laughter

the size of a walnut, malignant growth half a pinkie wide,

that hypnagogic state aware of its blood.

A community sweeps through a life. So

listen to other people, measure chill

by its assertion, its metastasis in the trees.

Time to grow up, you say to yourself,

over sixty now, over some of the silliness

which fueled ever after. One

way to recover walking stick art from sand

is to include tide and moon, starfish

at equinox, when earth interferes, refracts, when one

undergoes procedure which leads to knowledge but not yet.

Seeing It

Not seeing it that differently since Dr. Marcus gave me my short-life

sentence (metastases) last month, although going to a Christmas

concert (Jew or not, what's the difference) at the Methodist church

downtown, all the office buildings and restaurants (like ZOOP) (soup

with lots of garlicish, exotic cheeses zest), past the state capitol

building, all sorts of memories begin to surface from my deepsea

memory depths, similar streets in Brooklyn, L.A., Berkeley, Philadelphia,

Chicago, Buenos Aires, all my restaurant and zesty babe dates, all

the blossoming Debussy and Schuman pianos and tubas, if only I

could call my never-get-along-with Mom or made-out-of marble

Dad, the old babe-friends, too-long-dead pals like Bukowski

and Jorge Luis Borges, Neruda, memories almost becoming

incarnate, in-stone, in-brick, want there to be an infinity of forewards

that never

end,

end,

end.

Humming

Our father taught us

music too—

Saturday evenings,

the tubes grew hot

as the turn-table

ran across a needle.

Steady low strings

held the cut of high

strings, in the air

around the room.

We listened;

the hiss and hum

of Copland's

Spring, resonated

the speaker gauze.

We lay with him

on the carpet;

one of our hands

in each of his,

while notes pulled

new meanings

of what it meant

to be a hard-working

man, overcome

with such sound.

In free fall, the gang at Deutsche Bank threw him a wedding

to end all weddings. One microcosm after another

dedicated itself to abstract thought, gave up

"voluntarily" (according to reliable reports) its benefits,

its annual bonuses, its blackjack winnings.

Mukarribs on horseback swept through, leaving

predominantly Jewish sections of Brooklyn in a state

of disarray: portraits of Warren Buffett dashed

to the floor, babies skewered like

lamb kebabs. Plausible theories spring up all along

the perimeter of our municipality, bursting

the dam of our estrangements.

On Getting Home Early for a Change

Walking music to my ears, half-discovered anchovies

speak well of pizza, pal. Bring me tablet of water,

I sequestered. This is likely to be an illusion, as I often

said, hypothetical statements, always the first to go.

Failing to glide, the airplane plummets. Delicious

ending in contentment at the edge of far-flung fields.

Some friends stop by, but just to say hello, and,

having said hello, are on their way.

On Not Getting to Second Base

I met a traveler from the old country who said, "Two men down in the bottom of the ninth and no one left in the bullpen. A broken-bat single and we were alive again, ready to do some damage even though the baseline seats were nearly deserted. On the mound near the rosin bag, a pitcher's foot, half off the rubber, twists and paws the dirt. Over the shoulder, a wrinkled lip and cold mocking glance toward first. He stamped the rubber, shook the sand from his cleats, and nodded to the catcher after shaking off three signals. A passionate glare from the one who squatted behind the plate, and the wind-up began. Another glance at first. Beyond the pitcher's mound, beyond second base, beyond centerfield, the batter could see the statue and the words that appear at the base of the statue, below the pointing hand that mocked us: 'My name is George Herman Ruth, Sultan of Swat! Look at my work and despair.' Nothing left now of our season. Around the decomposing year, only that sinking feeling of one final failure: the crack of the bat in my hands, and the run, the tear around first and the final out, trying to stretch a single into a double. The long, slow walk to the clubhouse."

The Red House, Indiana

Aunt Gladys leads me to the house at the far end of the property, next to the radish garden. Bright red bricks of the tall two story house, the corn and soy beans bend in the rapid summer storms threatening to tantrum. Did I mention the air as thick as flannel sheets; the humidity like oxygen perspiring between teeth? Aunt Gladys educates me on why the window sills are as low as my knees. The narrow doorways—4 leading to the kitchen alone—remind me of an awkward teen I once met who didn't care if he survived the apocalypse. Later, I will be shown a pile of wood hiding in the grass which used to be a shack they lived in 60 years ago. When grandma's not around, I will be told of a shot gun barrel placed into a husband's mouth, the trigger pulled in front of his wife. In the morning, Gladys shows me how the horses bow their necks to her, lift hooves off the ground for her. I am introduced to 'Barn Cat,' the cat that lives in the barn. Were you aware Grandmothers squirm when their sisters tell their granddaughter stories about them that involve shotguns and snakes? In the kitchen, I am accused of being a vegetarian. Did you know, lettuce screams when you poor bacon grease over it? At night, I am handed a ledger her father brought home from work one day; I could tell one of the sisters—her cursive precise, tense, embossed—wrote songs to get her way, crooning about who she wanted to marry. I am told about the half naked girl running through their property in the middle of the night to escape boys in a blue pick-up. I notice the gun with a long barrel leaning on the bathroom doorway. After lunch, I'm given some white lightning from a mason jar in a locked cabinet. After a week, I begin to liken the house to an air conditioned coffin. I look forward to the bugs that light up at night, a temporary immolation. In the back of the red house, I find a room with floorboards missing. Aunt Gladys pulls open a small, square door on the side of the wall, revealing a crawl space that emits the smell of mold. It leads to a tunnel that opens to the road, she says.

The Born Again

My uncle calls to tell me God kills people because he hates them. Ever since he died for 2 minutes after his motorcycle accident, his God's become a vengeful God, a sniper with the best firing position in the universe. His God's out there right now getting revenge: unlocking doors, sneaking through living rooms, gliding knives over throats. My uncle's pissed God hit him with a mail truck and then kicked him out of eternity a couple minutes later, like target practice, leaving him breathless and bloody, with someone shining a light in his face, asking do you know where you are, Mr. Nelson, do you know what happened? and he did.

My Father's Wife

Now that I'm done putting her shoes on the proper feet, it's time to get her shirt on. Her left arm gets stuck, her eyes close, she whimpers. "It's ok," I say, guiding her wrist to the sleeve. I gave up on directive cues days ago; it's not like up means down; down is just the right shoe on the left foot; up is all dressed and time for CNN. Manerva is living proof that if you drink yourself to dementia and then want something done, I will have to do it for you for the rest of your life. On my way to the kitchen to do her laundry, the TV tells us a hurricane is blowing Texas into Ohio. I'm so glad I live in California. Why don't people evacuate when they have the chance? "I love you," Manerva says.

Taps, 5pm Sharp, Monterey Presidio

Everyday, 5pm sharp: Taps: a whisper creeping

up apartment windows, ocean front properties,

a thick mist curling like a question mark.

In case we forget, the military reminds us

it was here first: our land's worth in beauty

is only second to its strategic placement.

We live not on a bay with prehistoric pines

jutting from mountains, but a hill on which

to mount gun turrets.

Everyday at sundown, soldiers are saluting

like a psychic is predicting, only with less doubt

that somewhere a bullet took up residence

in a skull, a heart; shrapnel drilled a jugular.

Everyday at sundown, I know a soldier's

caught outside the mess hall, stuck saluting.

I'm not so sure what they think us civilians

are doing: setting our watches, I suppose.

I Study the Sky

how it changes,

a cloud, bursting, its colors,

fierce at first, fast disappearing.

Another brushes in, this whisper I can hear

forming and reforming,

silken mesh dissolving,

unraveled, rewoven.

My self is kin to this cloth,

these shades of pink, purple,

lavender, gray.

Then night sinks over

my cigarette's ember.

Its ash glows red in the wind.

Suppose Death Came,

a visitor through check point.

They'd strip search him,

ask his name, not recognize

the curl of his lip,

the waxy skull with no hair,

not know who he was—

his papers were good—

come for a look around,

a chance to greet

the weakest among us.

We welcomed him

as best we could,

someone with news,

someone from outside—

journalist, doctor, lawyer.

Later we learned

he was all of these and more,

face a kaleidoscope,

mouth a slit, a curl, an "O,"

full of lies we'd already come to know—

they came with the food,

the beds, the clothes.

These poems are from a chapbook titled This Whisper that is composed of selections from the journals of an imagined inmate being held without charge at Guantanamo Bay.

Landscape with Mower and Roses

I'm half in love with the girl

two houses down, pecking at her cellphone

while she mows the lawn.

As if someone might want to hear her

in this state: drowned by fumes,

her voice a small noise among noises.

But she'll locate someone, I'm sure,

do some talking at 95 decibals,

then hang up, do some singing

no one can hear. That will take an hour.

Then quiet will fly over like a cardinal

and her hands will tremble

because if there is a God

this is his ringtone, this shaking

and trembling and then quiet.

And heaven is a green, level place

at the end of the spiral she's been mowing.

And the day will go the way of cellphones,

the way of roses who run

to the end of their beautiful lives

and are left there saying what? What?

An Answer

after Ou Yang Hsiu

And no, spring continues

no matter what you've heard.

Last night a hard, March gale

grounded a flock of grosbeaks,

and now six males

with snaggled beaks

and red target throats

wrangle at the feeder.

Only force could have

brought them down.

We hope they are gods;

we hope they will hear us—

or at least grant us something

for our hospitality. Maybe

our skewed chimney

could be less skewed?

Truthfully, we would welcome

help from even minor gods,

even these drifters we know

will take advantage and then

leave. We are not dead yet,

but we will be buried here.

Korean Echoes

My turn had come;

Billy Pigg, helmet flown

lost, shrapnel more alive in him

than blood free as air,

dying in my arms.

Billy asked a blessing, none come

his way since birth. My canteen

came his font. Then he said,

"I never loved anybody.

Can I love you?"

My father told me,

his turn long gone downhill;

"Keep water near you, always."

He thought I'd be a priest before

all this was over, not a lover.

Morning Fog

Its dalliance with the earth

almost spent, the sun-disc

floating like a hole in a tree—where no one

is left sleeping

after a night like that—

its fingers lifting from what it touched

(to cure? to injure?) rooftops, fence posts

the shadow leaves of autumn—

it lifts up and away

as if late for the lecture of oceans,

this fugitive caught in the act

trailing lines of web, smoke, particles

grayed yellow by the scion

of age: milk-scored umbrella folding

back into its handle...

The Oyster Hills

I want to see the halved,

the looted,

the irregular,

the ones with perfect pearls

& those that house inclusions.

I want to hear gulls

screaming

in a hard wind,

pushed inland by the front.

To touch with my hands

that pat down linens

and fold

towels—

touch the sharp,

toothy old

houses for creatures

who were harvested

in droves.

Most of all I want

the smell of salt breeze—

to hold that hollow

in my chest

where air

rises and falls without

my consent,

& the flesh house

agrees to wear

and be worn down.

I want the pile

to grow

like a pyramid—

its yellow

truck having carried

one and another useless

treasure

in its incessant jaws—

the bulging meal

of empty shells

cursed

by the man in glass,

who knows a few things

about nacre.

I am aware that I am carrying whole family members, old friends around with me, psychologically speaking, and the concept of the "natural" me is probably a little ridiculous

Your assignment is clear

One day a man approached you on a city bus and stuck his penis into your hand Following proper procedure, you were completely still and sure not to put it anywhere

near your mouth. Eyes straight ahead.

Rabbits are prey so they must be very fast jumpers

You swing only one arm when you walk and whenever you want to kick the shit out of

someone for practical, instructional purposes or for the mere joy of it, you always

snap the rubber band on your wrist until the urge passes. You imagine eternal

walls of fire

You never ooze or excrete. You smell like polyester

When you arrive in hell, you'll pretend to have gotten there by accident; perhaps faulty

public transportation or inaccurate online directions

People often think it's okay to touch pregnant bellies, as if something that stands out so

far must be public property

When you were young, you rolled around with your friend, practicing being

heterosexual.

You grabbed and tickled each other coyly. When she fell asleep with her head

on your lap, you hoped she'd move a few inches to the right.

Some of them are white to camouflage into the snow

You always use a washcloth

You danced up close in the den; she promised not to tell

Rabbits have eyes on the sides of their heads

When you arrive in hell, you'll acquaint yourself with the locals like new neighbors on a

suburban street. They must have filed down their horns

Rabbits are always female in that way people assign gender to animals. Alligators and

dogs are male. Cats are female. And then rabbits. Although females don't

necessarily have eyes on the side of their heads

You didn't even move when the bus stopped

You ripped out the hospital corners

You love hierarchy

I find myself with very full weekends although socializing is never as comfortable as it is with people I've known several years

You have limbs like curling cigarette smoke—androgynous—that bitch wooden floor

beneath you

Your pride sleeps past the alarm, you drool, you don't get the joke. Time is not running

out, it's running away

You once spent 150 minutes banging your head. It was in fashion then

They say people like you compare your insides to other people's outsides

Outside a man masturbated while watching you trip on cracked sidewalks

You snap your hips like you're fucking. Not then, but now. You don't know what to do

with your arms; you wish you had a handsome carrying case for them. You touch

no one despite the fact that they sometimes touch you. You move to your right

better; your ass has an audience

You startle easily; the man didn't care you were not old enough to masturbate to in public

Getting help makes you tired. Birth control is a burden

What do you say to the neighbors when you run up to their door because you just saw a

man with his dick in his hand? You can ask to come in or you can ask to borrow a

cup of sugar or you can say, "This man out there has his thing in his hand and he's

sitting on your car. That's your car right? The dark blue one in front of your

house? He's there." And then you turn and he's gone

You must have been important; he didn't want to be without you

Your head is a dozen Tonka trucks being banged by petulant children. Undiagnosable.

It's never bright enough through the fog and night visits longer than expected

No one really borrows sugar in real life

As you become smoke, you know your skin is forming a shell, making you solid. Your

time in gaseous phase is short—sublime that way

While driving home from a lover's house, you remember pictures taken in the bathtub

you choke on an Altoid and pull over to Heimlich yourself over the edge of the

open car window

One day your skin will crack if you try to move

You'll let yourself stay in bed because nothing outside is as satisfying, a long life will be

a testimony to your intellect, caught, not irrevocably but possibly permanently

You drool out the Altoids. That man's penis is more real than the sugar, more real than

the diagnosis

You won't give them back